ZEINA BALTAGI

THE SIDEWALK

text by Elizabeth Skalka

A manipulator of image and form, Zeina Baltagi operates outside the boundaries of medium and beyond the description of the term ‘sculptor.’ Her work is multifaceted, containing within it elements of performance, installation, and sculptural construction. In the same way, Baltagi’s identity, as well, defies categorization. Raised between Lebanon and the West Coast of the United States, she is a citizen of both countries. In her cross-disciplinary practice, she grapples with her sense of movement, mobility, and selfhood.

What is fundamental to Baltagi’s work is the exploration of the immigration experience. Speaking on her own childhood, Baltagi has noted that when migrating to a new country, one might feel a sense of guilt, that they have abandoned their home for a quieter life. Her sculptures in The Sidewalk series address the tension between the tranquil suburbs and the intrinsic drive to fight for justice in the SWANA (South West Asian/North African) region. She cites as a major influence Judith Butler’s concept of precarity, which can be defined as the “unpredictable cultural and economic terrain and conditions of life” as experienced by “marginalised, poor, and disenfranchised people who are exposed to economic insecurity, injury, violence, and forced migration.” Though precarity can be encountered anywhere, Baltagi has found it to be inextricably linked with the public sidewalk. The sidewalk exists at the intersection of the private and the public, it can be a place of community gathering — often the site of protest and demonstration — but it is also a place where people, especially people of color, can find themselves in danger. Through her work, Zeina Baltagi explores the ways that sidewalks are political and social devices, where both their meaning and their function are intrinsically tied with the assimilation of immigrants and disability and accessibility politics.

In her series The Sidewalk, Baltagi assembles four concrete-based constructions reinforced with rebar inserts. The three smaller works consist of concrete panels, posed and layered with keffiyeh cloths, which both symbolize political resistance as well as the artist’s own heritage. One such work, I’m Spinning, includes a rotating element, and documentation of the sculpture in Baltagi’s studio shows her standing atop the concrete tile as it spins rapidly beneath her. This particular piece ties in with the concept of Diasporic Vertigo, a theory developed by Professor Valorie Thomas, deriving from Butler’s idea of precarity. Thomas explains that, in Diasporic Vertigo, “artists prophetically engage the impact of being dispossessed, fragmented, and disrupted and at the same time utilize vertigo as a portal that yields the knowledge to be found in disorientation, self-generated equilibrium, and attunement to inner balance.” In I’m Spinning, Baltagi illustrates that vertigo literally, planting both feet on a concrete slab which whirls her body around, completely beyond her control. This sense of motion mirrors, in some ways, Baltagi’s description of migration, in which one is forced to flee their home due to political circumstances. In such cases, there is a feeling of powerlessness and displacement, the effects of Western imperialism which begin to splinter the notion of home. The coming together of this fractured sense of self, the reunification of one’s identities, produces the effect of Diasporic Vertigo. For Baltagi, home is Lebanon, California, and the spaces between, and in this state of multiplicity she continues to grapple with the discomfort of living in a country which harms her motherland.

I’M SPINNING

I’M SPINNING

Materials: Concrete, rebar, steel spinning wheel, and keffiyeh scarves.

Dimensions: 50 x 50 x 8 inches

Above: Photograph of a sculpture by Zeina Baltagi called I’m Spinning. The sculpture is made up of two square shaped slabs of concrete stacked on top of each other, each with a red and white patterned keffiyeh scarf laid out underneath it. The top slab is rotated about ninety degrees so the corners of the bottom slab are visible.

Left: Zeina Baltagi is standing on top of her sculpture called I’m Spinning. She is wearing blue Lee Can't Bust Em 1940s Union cover-alls, and tan work boots, with a red and white patterned keffiyeh scarf around her neck which covers her nose and mouth. The top slab of concrete and the attached keffiyeh scarf are spinning rapidly, while the bottom slab and keffiyeh scarf are completely still.

Beyond the themes of immigration, The Sidewalk series also directly references disability culture and the accessibility concerns that those living with mobility impairments face when moving around public spaces. One in four people in the United States have some type of disability, and the most common kinds of disabilities involve moving or walking independently, but often, accessibility measures are seen as an afterthought, if they are considered at all. In Trip Hazard, Baltagi embeds yellow detectable warning tiles in the surface of the concrete slabs, replicating the way they would be used on a train platform or the curb ramp of a sidewalk. The slabs face each other, and are connected at the center by keffiyeh clothes wedged into horizontal slats on the base of the concrete. Since yellow warning tiles are used to indicate an entrance, exit, beginning, or end, Trip Hazard has no clear start or end point. Baltagi’s preoccupation with beginning and end points is present in all her work, as she is constantly concerned with how to move from point A to point B. This is true not only in her artistic practice, but in her daily life as well, as her right leg is fitted with an endoprosthetic tibia, knee, and femur which alters her range of mobility. When approaching any new landscape for the first time, Baltagi and others in her position must scope out the terrain, calculating how best to navigate the space.

TRIP HAZARD

TRIP HAZARD

Materials: Concrete, rebar, keffiyeh scarves, and yellow detectable warning tiles.

Dimensions: 36 x 115 x 48 inches

Above and left: Two installation photographs of the sculpture Trip Hazard by Zeina Baltagi. The sculpture is comprised of two concrete slabs, one propped up against the wall and the other lying flat on the floor. The slabs have a slope at 4 inches at its raised side and 2 inches on its lowest. Rectangular sections of yellow detectable warning tile are embedded in the surface of each concrete slab, taking up half of the surface area. The bare concrete sections of each slab are facing each other. Halfway down each concrete slab, beneath the section of yellow detectable tile, the slab is split widthwise, making a deep slit in the thin base of the slab. Keffiyeh scarves are embedded into the slits, connecting the two slabs.

Because of her combined interest in disability justice, immigration narratives, and the political nature of the public sidewalk, Baltagi has found a particular fascination with suburban neighborhoods, especially those featuring cul-de-sacs. The notion of the suburb, in which those with means are able to remove themselves from the larger population in a kind of self-segregation, often designates such neighborhoods as “safe spaces” for the wealthy and white. Its lack of accessibility is not only intentional, but integral to the function of the suburb. For immigrants like Baltagi and her family, moving to neighborhoods like this means erasure of their roots as they begin to assimilate to the local culture.

The cul-de-sac, a passage which is closed at one end, precisely exemplifies the principles of a suburb. It is a dead end, it provides no access or direction, and only those who are supposed to occupy the space are allowed, deeming all others trespassers. Even the word “cul-de-sac” indicates its exclusivity. Used in medical textbooks to reference pouches in the uterus, the term calls to mind the safety and comfort of the womb. In her series The Sidewalk, Zeina Baltagi carefully considers each of these elements in a critical examination of the politics of suburban life.

The largest work in The Sidewalk is an actual paved sidewalk installed on location on the UC Davis campus in California. The horseshoe shaped path is embedded in a cleared out patch of land in a wooded area, away from any roads or buildings, and nestled in the curve of the walkway is a large bay leaf tree. Titled Daphne, the installation is a contradiction of simultaneous accessibility and inaccessibility. Though the work is public, free to visit, and ADA compliant, it is also isolated, and removed from any path, thus proving difficult or impossible to reach if relying on a mobility aid.

DAPHNE

DAPHNE

Materials: Concrete, rebar, and sand.

Location: The Domes, Baggins End, Davis, CA 95616

Coordinates: 38.543143,-121.765510

Above and left: A series of four photographs depicting the installation Daphne by Zeina Baltagi. Each photograph features a horseshoe shaped paved sidewalk in a cleared out dirt patch of a wooded area. Inside the U of the horseshoe shaped sidewalk, a tree grows out of the ground. Three of the photographs include blurry images of Zeina Baltagi in motion, walking on the sidewalk. She is wearing blue Lee Can't Bust Em 1940s Union cover-alls, tan work boots, and a red and white patterned keffiyeh scarf over her face.

Baltagi considered several different factors during the creation of Daphne. First, as in all the works in The Sidewalk, she contemplated the political nature of the public sidewalk as it pertains to immigrants, disabled people, and people of color. Sidewalks are integral for moving about the world, but for those whose very existence has been politicized, public spaces, especially those which exist on the cusp between public and private, can carry a greater meaning. Particularly in suburban neighborhoods, private citizens tend to feel ownership over such spaces, perceiving all outsiders as a threat. Even in urban areas, groups of marginalized people who rely on sidewalks and train platforms to get where they need to go can feel edged out by those who feel more deserving of claim to space. In Daphne, Baltagi makes this divide exceedingly evident. She has removed the cul-de-sac from its quiet suburban landscape and placed it in a forested alcove, where all who visit can experience it through the eyes of an outsider, someone to whom this space does not belong.

Another major influence on the work is the Greek myth of Apollo and Daphne, for which the installation is named. The story, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, tells of the god Apollo who, enchanted by Cupid’s arrow, pursues the water nymph Daphne. Daphne, also under Cupid’s spell, is repulsed by Apollo, and continuously spurns his advances before being chased by the god in a foot pursuit. As Apollo closes in on her, Daphne, out of options, begs for help from her father Peneus the river god, and as Apollo wraps his arms around her, Daphne’s body morphs into the shape of a bay leaf tree. Even once she has been transformed, Daphne is not safe from Apollo’s grasp. He vows to make a wreath out of her leaves, and a lyre from her branches. Daphne, eternally rooted in place, still cannot escape her captor.

Zeina Baltagi makes specific references to the myth, both through the title and through the inclusion of a bay leaf tree. Since the tree rests in the center of the U shaped sidewalk, the cul-de-sac can be read as an interpretation of Apollo wrapping the nymph in his clutches. For Baltagi, the story of Daphne contains personal meaning, as the notion of a woman being immobilized by a man echoes themes of disability justice. Daphne is disabled twice: first when she transforms into a tree, and again when Apollo dismembers her, stealing her leaves and branches. Women, especially those who are disabled and chronically ill, experience loss of control and the theft of their autonomy every day. Through the incorporation of the myth of Daphne, Baltagi calls attention to the ableism and sexism ingrained in our very culture.

In addition to the political and mythological motifs in Daphne, the work also follows distinct art historical traditions, making nods to past performances, sculptures, and installations. For one, the notion of a pathway with no start, end, junctions, or appendages recalls the work of minimalist American artist Carl Andre. Known for his interactive flat sculptures, Andre spent much of his career developing gridlike tile forms whose linear designs evoke a road to nowhere. As a formal structure, Andre’s work closely resembles Baltagi’s. Both incorporate segments of roads or pathways, welcoming viewers to stand upon them and experience them from multiple points of view. However, when discussing the work of Carl Andre, it is important to to address his personal history as well, namely the 1985 falling death of his wife, artist Ana Mendieta, for which Andre is generally agreed upon as the perpetrator. Andre’s reputation as an abuser and potential murderer of women provokes a further lens with which to view his connection to Baltagi’s work. Having considered themes of assault and misogyny through the story of Daphne, Baltagi improves upon Andre’s formalist perspective by incorporating a feminine critique of minimalist art.

Carl Andre, Equivalent VII,1966. © Carl Andre/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2022.

Another artist to whom Baltagi makes specific reference is conceptualist Pope.L. Beginning in the late 1970s Pope.L staged a series of performances, which he called “crawls,” in which he inched his way through the streets of New York while crawling on his knees. By forfeiting his “verticality,” Pope.L forced onlookers to look down at him literally, bringing attention to the class divide which persists in public spaces. Often performed in a business suit, the crawls underscored the futility of hard work in a society that rewards the privileged. Aside from the obvious connection to Baltagi’s interest in publicness and accessibility, Pope.L’s crawls set a precedent for the activation of space which Baltagi builds upon in her own project. In documentation photos that capture the setting and layout of Daphne, blurred images of Baltagi in motion can be seen in front of and walking on the surface of the sidewalk. The photos suggest to viewers that not only can the structure be interacted with by audiences, but that there is some sort of performance aspect that goes along with it. As in Pope.L’s crawls, Baltagi animates her work by incorporating motion, gesture, and ritual.

Pope.L, How Much is that Nigger in the Window a.k.a. Tompkins Square Crawl, 1991

One project that seems particularly in line with this combination of still image with choreographed movements is a recent series by Janine Antoni called I am fertile ground. Installed on site at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, the series consists of nine photographs in gilded plaster frames. The photographs depict parts of Antoni’s own body and those of her aging parents, and the accompanying frames are sculpted from medical models of the bones in each respective photo. Thus, an image of Antoni’s mother’s hands with palms pressed together sits in a frame made from the imprint of finger bones, both pressed into and dragged through the plaster mold. On their own, the framed photographs are stunning icons and, placed in their own niches in Green-Wood’s catacombs, they give off a divine, even sacred intensity. However, there is more to these works than the physical objects alone. Each of the nine photographs represents and is paired with a specific gesture and spoken mantra designed by Antoni. The image of Antoni’s mother’s hands, for example, corresponds with a gesture in which one turns their fingers inward to their chest, splays their hands outwards, as if blowing a kiss, lifts their palms up by the crown of their head, and presses their fingers together, meeting at their lips. While performing the gesture, one repeats the phrase, “The water flows over me. The water reflects in me. I mirror the water. My waters rest.” The project is not simply a series of photographs, but a full body immersive experience in which each component together makes up the artwork.

Janine Antoni, I am fertile ground the Catacombs at The Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, 2019. © Janine Antoni. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco. Photo: Christopher Burke.

In Zeina Baltagi’s Daphne, the protocols which make up the performative elements are not as clearly defined. While documentation photographs show her moving around the space, there is more than one way to activate the installation, and the photos seem more like a record of a one-time happening. Still, as in Antoni’s project, the question persists of what is the artwork and what is merely a stand in.

This question has arisen for artists since the development of performance art, beginning in the 1960s and ‘70s with artists like Vito Acconci. In the fall of 1969, Acconci recorded the process of himself following strangers around New York City through photographs, maps, and handwritten notes in a work he titled Following Piece. The work begged the question, what is the work of art? Is it a performance — the action of following passersby? Or is it the resulting documentation that lives on as a record of the event? It is a query that emerged often in the evolution of performance art, and again with the establishment of Fluxus. In a 1971 piece by Chris Burden, the artist filmed himself being non-lethally shot in the shoulder in front of a live audience. He later presented the work, called Shoot, via documentary photography, film, and written text. Around the same time, a movement called Fluxus was taking shape throughout international circles. Stemming from Neo-Dadaism, Fluxus was a network of artists who operated across disciplines, examining the roles of maker and object. Such artists, including Alison Knowles, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and Joseph Beuys, looked at musical scores and their ability to record instructions which could be reproduced by any musician. Thus, the work they produced was not fine art in the classical sense, but a set of directions which, when performed, would generate a work of art. Many such works have never been performed, but the object, the scrap of paper listing the instructions, exists as an artwork in a collection.

Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969

Alison Knowles, Shoes of Your Choice Event Score, 1963. Photo: Event Scores published by Left Hand Books, Barrytown, New York.

Shoes of Your Choice

A member of the audience is invited to come forward to a microphone if one is available and describe a pair of shoes, the ones he is wearing or another pair. He is encouraged to tell where he got them, the size, color, why he likes them, etc.

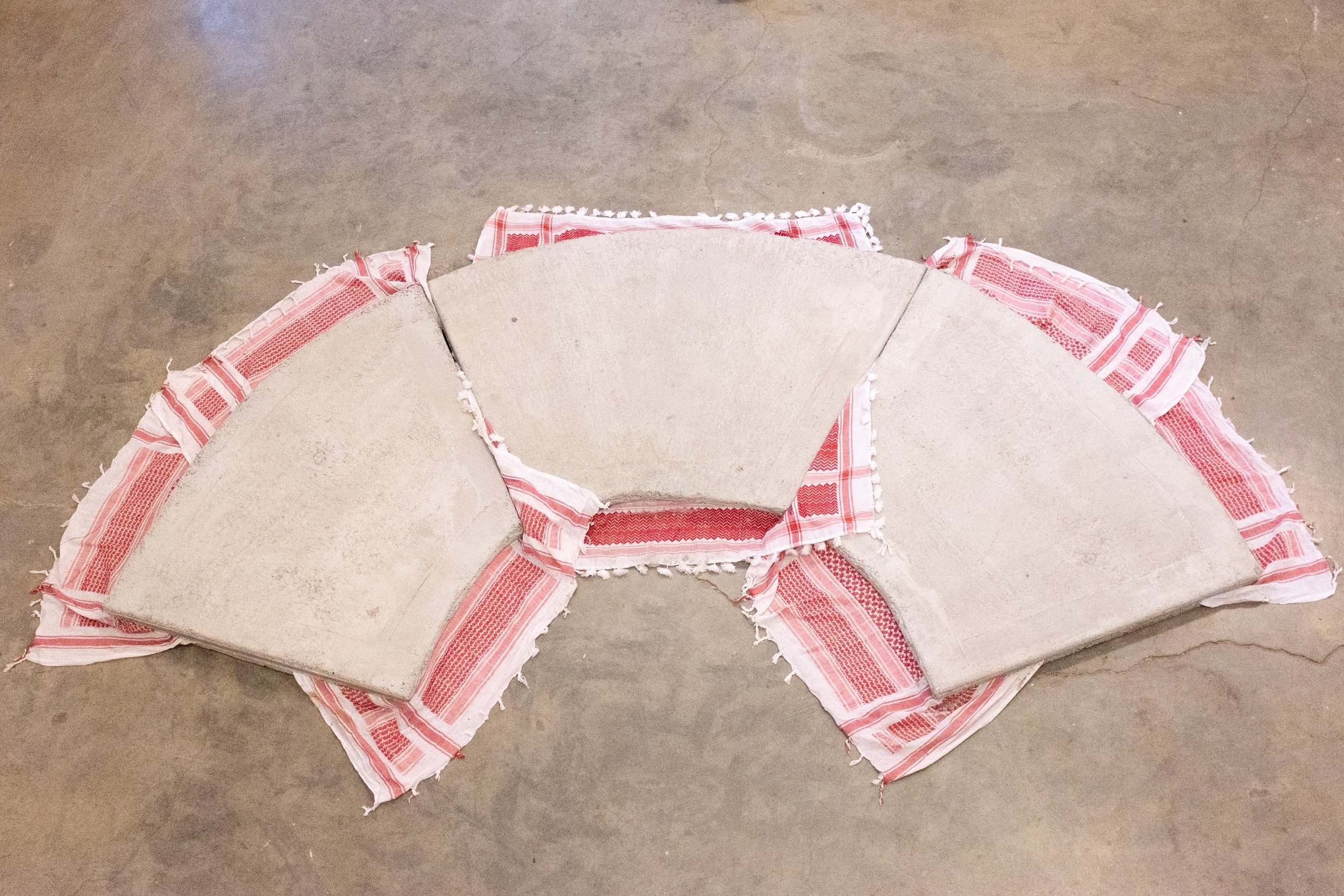

LAYERS OF RESISTANCE

LAYERS OF RESISTANCE

Materials: Concrete, rebar, keffiyeh scarves, and embedded ¢ents w/ 1¢ent dated 2001 on the surface.

Dimensions: 60 x 130 x 3.5 inches

Above: A photo of the sculpture Layers of Resistance by Zeina Baltagi. The sculpture is made up of three identical segments of concrete slab which are laid side by side to create a concrete semicircle with two seams where the segments meet. Underneath each concrete segment is a red and white patterned keffiyeh scarf embedded halfway through the slab. Corners of the scarves peak through the seams of the concrete semicircle and in between the slabs as the expansion joints of the sidewalks seams.

Left: A detail photo from Layers of Resistance. The photo is a close up of one of the concrete segments, where a US penny has been embedded into the surface of the concrete. The penny is dull and partially obscured by a dark spot on the surface, but the date 2001 is visible.

For Zeina Baltagi and the works which make up The Sidewalk, object, performance, and documentation are similarly called into question. Daphne continues to exist as a permanent installation in Davis, California, but is it a complete work of art if it isn’t being activated by a subject in motion? Even more puzzling is the question of the remaining three works in the series which, while documented in photographs of the artist’s studio, have since been destroyed. Indeed, there once existed two complete cul-de-sacs, one which lives on in the form of Daphne, and the other whose components make up the sculptures I’m Spinning, Layers of Resistance, and Trip Hazard. After being displayed briefly in a studio exhibition, each sculpture was smashed by Baltagi with a sledgehammer. Now, the works only exist in archival images and video of the destruction. So in addition to the question of what makes the artwork, the destroyed objects represent a further quandary: is demolition a part of the work?

Baltagi’s process of production, documentation, and ultimately destruction calls to mind an installation made by Kara Walker in 2014. Titled A Subtlety, the installation took place inside Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Factory, with the set intention of being demolished along with the building. Walker filled the factory with fifteen lifesize sugar statues of young boys carrying bananas and baskets, enlarged versions of blackamoor figures that she found online. Beside the fifteen statues, and taking up most of the space, was an enormous 75 foot long 35 foot tall sphinx, carved from blocks of pure Domino sugar. Combining features of the traditional Egyptian sphinx with the face of an archetypal mammy character, the sphinx addressed notions of racism and exploitation which are typical of Walker’s work.

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, 2014. Photo: Andrew Burton, Getty Images.

While audiences knew that the factory with all the sculptures inside was to be destroyed following the run of the show, they were unaware that Walker had secretly filmed the entire exhibition. Years later, all that remains of the work are one arm of the sphinx which was preserved, and the hidden camera footage which Walker has titled, An Audience.

Following in Walker’s footsteps, Zeina Baltagi has created a project with a beginning, an end, and a lingering documentation, an account of the life of the work. The Sidewalk emerges out of the tradition of early performance art, existing within the ambiguous boundaries of Fluxus. In each of the sculptural components of the installation, Baltagi engages with every part of herself, while also reaching backwards, embedding art historical references and disability politics which can be understood by audiences of all backgrounds. Through a series which examines the subsistence of immigrants and those living with disabilities, Baltagi has produced a body of work which is utterly human, tapping into the obstacles and grievances of those who share her experience. At the same time, she expands upon a decades long history of performance and installation, making it uniquely her own. Baltagi has ingrained her very identity into the fabric of her artistic practice, developing her voice and contributing to a new generation of makers hoping to diversify and humanize the world of art.

THE DESTRUCTION OF I’M SPINNING

DESTRUCTION

Above: A bird’s eye view of the sculpture I’m Spinning after it has been destroyed by a sledgehammer. Two square shaped slabs of concrete layered with keffiyeh cloths are stacked, and the top slab is rotated 90 degrees so the corners of the bottom slab are visible. There is a large dent in the center of the top slab, with five distinct cracks stretching out from it.

Left: An image of Zeina Baltagi swinging a sledgehammer at the sculpture Layers of Resistance. In the bottom left hand corner, the semicircular sculpture sits on the floor of Baltagi’s studio, and on the right, Baltagi, bent at the waist, is swinging the sledgehammer over her head, bringing it down upon the concrete. She is wearing ripped blue jeans and a light blue tunic with white trim, her hair is pulled back in a ponytail. A section of the sculpture Trip Hazard can be seen near her heel.

THE ARTIST IN CONVERSATION WITH THE CURATOR

Zeina Baltagi (b. 1988, Stockton, CA) is an artist, educator, curator, and programming director of Coaxial Arts’ Foundation. Baltagi was raised between California and Lebanon. The work reveals intimate realizations; transforming how Baltagi navigates herself in relation to physical, emotional, economic, and cultural mobility.

Zeina Baltagi received a B.A. from California State University, Northridge, and an M.F.A. from University of California, Davis. Baltagi has exhibited her work at galleries including Basement Gallery, Davis, CA; PØST, Los Angeles, CA; Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Hollywood, CA; bG gallery, Santa Monica, CA; Axis Gallery, Sacramento, CA; as well as at institutions such as the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA; California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, CA; and, California State University, Northridge, CA. Baltagi’s complete CV can be accessed on her site (link below).

VISIT DAPHNE

UC Davis Land Acknowledgement Statement:

UC Davis pays homage to the indigenous people and land on which the Davis campus is located. Following consultation with members of the Patwin native community, the campus is pleased to provide the following "Land Acknowledgement Statement" that can be used in oral or written form at events as deemed appropriate. The campus encourages those who are interested to use the following language, without edit:

“We should take a moment to acknowledge the land on which we are gathered. For thousands of years, this land has been the home of Patwin people. Today, there are three federally recognized Patwin tribes: Cachil DeHe Band of Wintun Indians of the Colusa Indian Community, Kletsel Dehe Wintun Nation, and Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation.

The Patwin people have remained committed to the stewardship of this land over many centuries. It has been cherished and protected, as elders have instructed the young through generations. We are honored and grateful to be here today on their traditional lands.”

https://diversity.ucdavis.edu/land-acknowledgement-statement

THE SIDEWALK IMAGE CATALOGUE

Townsend extends special thanks to Elizabeth Skalka and Zeina Baltagi for their generosity and contributions to Townsend’s presentation of THE SIDEWALK. Photographs throughout by Nathan Jorgenson IG: @fotoapparatic and courtesy of Zeina Baltagi.